An In-Depth Look at Heritage’s Wampanoag-style Garden

By: Amanda Wastrom, Curator and Iris Clearwater, Senior Gardener

Over hundreds of generations, Wampanoag people in this region developed a migratory cycle of living that followed the patterns of the climate and the land. They learned what resources were available and when. In Pup8n (winter), a typical Wampanoag village community would live in an area that offered protection from harsh weather like snow, high winds, and strong storms. During the warmer months of Seequn and Neepun (summer), farming is a key part of Wampanoag life. Combining farmed vegetables with foods for which they can hunt and fish (such as deer, turkey, fish, and shellfish), creates a nutritious, balanced diet.

Following the Seasons

The appearance of schools of spawning fish in rivers and streams as the water warms is one of the first signs of Seequn (spring) in our region. It marks a transition time, when families would move to their summer planting grounds. In a Wampanoag village, each family would be allotted its own section of land, approximately one to two acres.

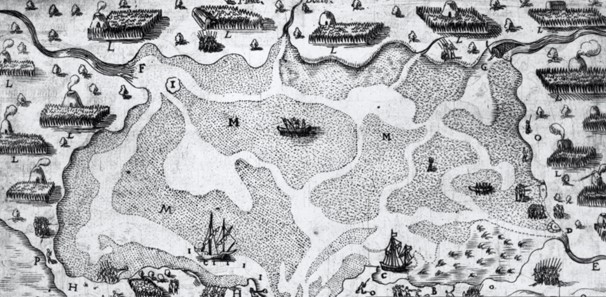

A detail of Samuel Champlain’s 1605 map of what he called “Mallebarre,” which is now known as Cape Cod. Wampanoag summer planting grounds can be seen depicted all along the shore, with each wetu having an adjacent planting field.

As life givers, Wampanoag women are the ones who fish, forage for wild-grown foods, and work the gardens. As the season progressed, tasks would vary from planting to weeding, harvesting, and storing for winter.

Meet the Three Sisters

Surrounded by forests, with limited land for farming, the Wampanoag developed a technique where many plants could be grown together. These three plant sisters—corn, squash, and beans—are a perfect combination. They provide a mix of essential nutrients and minerals, and each one helps the others to grow. Their long storage life is ideal for use in Keepun (fall) and Pup8n (winter).

Weeâchumuneash (corn)

As the eldest sister, Corn stands tall and strong in the center, providing tall poles for the bean vines. As a life-sustaining food, corn is a main source of protein and can be ground and used for flour. Corn is an integral food and the phases of the plant’s life cycle–such as when to plant, weed, first ready for harvest (known as ‘green corn’) and maturity–mark important moments in the summer cultural traditions.

Tutupôhqâmash (beans)

As the giving sister, Beans (usually runner or pole varieties that climb) fix nitrogen in the soil,. Nitrogen is an essential nutrient that the other plants need to grow. She also binds all three together as she grows up towards the sun.

Mônashk8tashqash (squash)

The next sister, Squash, grows sturdy and steadfast, providing shade and blocking weeds with her large leaves. The spiny hairs on her vines deter pests. Varieties such as pumpkins and winter squash are nutritious and long-lasting.

Namâhsak (fish) as Fertilizer

Fish is a plentiful resource in this region, not just as a food source, but also as an effective fertilizer. Namâhsak (fish) placed in the soil before seeds are planted provides nutrients and minerals for the plants as it decomposes. A challenge with using fish as a fertilizer is that it would be very appealing to animals and constant vigilance was required to keep them from digging up the fish. It is believed that fish would only be applied if the soil was exhausted and tired.

Heritage’s Wampanoag-style Garden

Inspired by Wampanoag farming techniques, Heritage’s Wampanoag-style garden includes a mix of traditional and contemporary plant varieties, creating a community of mutually beneficial plants anchored by the Three Sisters. In Heritage’s modern re-creation, we honor the Wampanoag tradition of women performing the farming by having female-identifying horticulture staff work on the garden. When needed, we amend the soil with compost and use a liquid, organic fish fertilizer.

The garden is three years old, so we are still experimenting with which heirloom varieties work best in our location. Each year, we plant King Philip Corn, a northern-adapted variety that has been grown by the Wampanoag for hundreds of years. This variety is named after a Wampanoag Intertribal leader Metacom, who was known to colonial settlers as King Philip.